Bicycle use soars after confinement, but there’s a caveat to the story

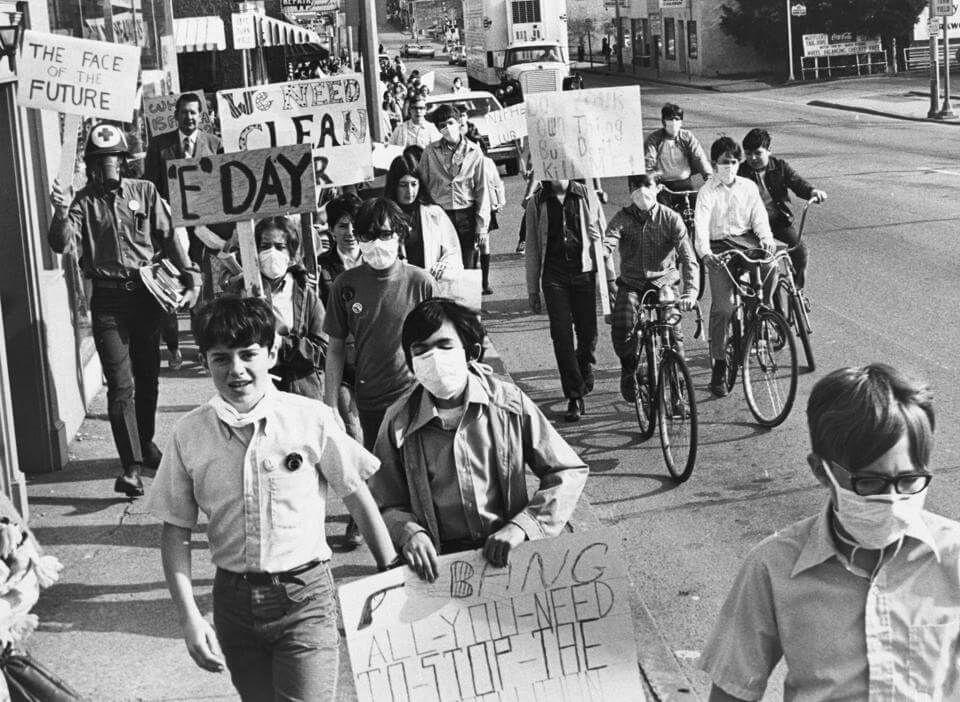

Students from St. Louis, Mo. St. Louis marching against air pollution

Translation of the original text by Carlton Reid published at Forbes.com

The motorists of the world should be afraid, the almighty bike lobby (if it existed, except as a parody on Twitter) is coming to take down the auto industry. Bicycle sales have skyrocketed since April 2020; space for motorists is being reclaimed overnight by global cities installing pop-up bike lanes; and car traffic levels due to confinement and working at home become similar to those of the 1950s, means more people are cycling, even on roads that just a few months ago were jammed with traffic.

Has cycling ever been so popular? Yes. In the early 1970s. It was then that much of the world, but especially the United States, experienced a “bike boom”: sales were so strong that bike stores regularly ran out of stock and prospective customers had to put their names on long waiting lists.

Built on the wealth of the baby boomer generation, growing environmental concerns and the same health drive that saw the rise of jogging, (who doesn’t remember Forrest Gump) this bike boom lasted about 4 years and was much bigger than the next industry BOOM coinciding with the explosion of mountain bikes in the 1980s.

Many commentators at the time believed that the boom would never end and that automobiles would forever end their hegemony. (Regarding the current bicycle boom, the BBC asked on April 30, “Are we witnessing the death of the automobile?”)

In the 1970s, U.S. bicycle advocates assumed that the United States would soon become more bicycle friendly than the Netherlands. But while the Netherlands used the oil embargo to curb the dominance of the automobile in its cities and expand its network of bike lanes, there was no lasting legacy for the US. The boom exploded, and now few remember the U.S. bicycle craze of the early 1970s.

Contenidos

- 1 How did the boom happen, why did motoring regain the upper hand, and what are the lessons for our post-pandemic future?

- 1.1 Bicycle Sales in the 1970s in the United States

- 1.2 Ecological concerns were one of the drivers of the boom.

- 1.3 The perfect machine

- 1.4 Richard ‘s Bicycle Book

- 1.5 “Factories don’t make bicycles fast enough.“,

- 1.6 Coronavirus pandemic causes anxiety and changes in routines in the U.S.

- 1.7 Period graph showing the rise and fall of bicycle sales in the 1970s.

- 1.8 “The boom has turned into a bust.”,

How did the boom happen, why did motoring regain the upper hand, and what are the lessons for our post-pandemic future?

Excerpt from Life magazine, 1971 LIFE, 1971

“CROWDS PRESS in Chicago’s Turin Bicycle Co-op looking for new models,” Life reported in July 1971. Under the title “The Bicycle Madness“, the Life article featured a double-page photograph of a diverse crowd waiting to buy bicycles: men and women, black and white, young and old.

“So far this year, Turin has sold more than 3,000 bicycles and could have sold several thousand more if supplies had been available,” the magazine continued.Bicycle sales in 1970 increased so rapidly that Time claimed that it was the “biggest wave of bicycle popularity in its 154-year history“.

This was not to everyone’s liking: Peter Flanigan, a Wall Street investment banker and one of President Richard Nixon’s most trusted aides, chided that, “America is not going back to cold, dark and bicycling.” He was soon proven wrong, at least about cycling, and even some of President Nixon’s closest confidants fell under the cycling spell.

Cyclist celebrating Earth Day

Bicycle Sales in the 1970s in the United States

“Harvard English professor Joel Porte sold his car four years ago and hasn’t even been tempted to own one since,” explained newsmagazine “Instead, Porte, 36, and his wife Ilana, 31, get by on English three-speed bikes; they make the trip from Belmont, a Boston suburb, to the Cambridge campus in 17 minutes.

TIME continued, “Last week, just before her first baby was born, Ms. Porte was still running errands on a bicycle. Doctors and professors at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland often travel by bicycle, as do some members of the Cleveland Orchestra, with piccolos, flutes, violins and violas strapped to their backs.”

Cycling made its way into the mainstream during the boom years of 1970-1974. “Some 64 million fellow commuters regularly ride bicycles these days, more than ever,” Time commented, “and more than ever [están] convinced that two wheels are better than four.”

A Bank of America report said bicycle sales had been “chugging along” at 6 million a year “until the boom began.” In 1971, sales increased by 22% to 9 million and reached 14 million in 1972. The following year, this figure increased even further to 15.3 million, most of the increase was due to the sale of bicycles for adults.

The boom was rural and recreational, but also urban and practical. High-ranking politicians, some of whom were cyclists, told planners to keep building miles and miles of urban bike lanes.

“Both national and local governments have recognized the phenomenal growth of bicycling,” Time reported, “and the Interior Department has plans to build nearly 100,000 miles of bike lanes over the next ten years.”

“If this plan had been carried out, it would have dwarfed the Dutch bike lane network.”

In 1973, 252 bicycle-oriented bills were introduced in 42 states; 60 became law, half of them bike lane bills. The Federal-Aid Highway Act of the same year provided $120 million for bike lanes over the next three years.

The resurgence of the bicycle had taken most observers by surprise. What had been an “exiled device, to be used somewhere between kindergarten and acne,” Time claimed, became a mode of transportation to be reckoned with.

“Bicycles are back,” stated Noel Grove, editor of National Geographic, in the May 1973 issue of the magazine.

“Overcrowded roads, ecological concerns, the quest for healthy recreation and the sophistication of geared machines have contributed to an avalanche of cycling activity,” Grove explained, adding that “legislators are beginning to think about bike lanes as much as highways.”

His twelve-page article concluded that “with bikeway construction and ecological concern marching hand in hand, the U.S. bike boom could herald a whole new era in transportation.”

960×0 3

Woman in gas mask with flowers in her hair

Bicyclist on Fifth Avenue, New York City, during Earth Day festivities, 1970. BETTMANN ARCHIVE

Ecological concerns were one of the drivers of the boom.

During the “Summer of Love” in 1967, San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district reeked of patchouli oil, grass and incense. With flowers in their hair and buzzing with “acid,” some of the area’s self-described “fanatics” protested not only against the war but also against the waste.

This concern deepened for many, and for those “hippies” who became environmental protesters, the automobile became a potent symbol of all that was wrong with the “military-industrial complex.” In February 1970, nineteen ecologically conscious humanities students at San Jose State College bought a new Ford Maverick and, with their professor’s blessing, buried it in a 12-foot-deep hole dug in front of the campus cafeteria.

This crowd-funded destruction of the hated automobile made headlines around the world. With six students on the roof of the car, “it was pushed through downtown San Jose in a parade led by three ministers, the university band and a group of attractive students wearing green shroud-like robes,” reported the San Francisco Chronicle.

“As the local citizenry watched from the sidewalks, the students marched to a slow funereal beat set by the band playing a selection of songs in flimsy styles.”

960×0 2

April 22, 1970, April 22, 1973, September 23, 1974; Bicyclists demonstrate near the state Capitol during 1970 Earth bicyclists demonstrate near the state Capitol during Earth Day 1970. (Photo by Duane Howell / The Denver

The burial was one of the events organized in the run-up to the first Earth Day on April 22, 1970. the first Earth Day on April 22, 1970.

For many event organizers, the automobile was public enemy number one. An event guide published by Friends of the Earth included a chapter entitled “Warning: the automobile is hazardous to earth, air, fire, water, mind and body”.

And if the automobile was the problem, the bicycle was the solution. The Earth Day coordination team suggested forty ideas for Earth Day events; one of them was “Encourage people to walk or bike instead of driving cars on April 22.” Twenty million Americans participated in a variety of events on the day itself and the months leading up to it, many of them held in colleges, schools and universities, was the first “green” generation.

“Bicycles are small, inexpensive, require little maintenance, are pleasant to use, and cause no pollution. “, Whole Earth Catalog stated for 1970, adding, “If America switched all of its [coches] to bicycles, many problems would be solved.”

The perfect machine

In an article on bicycle technology that appeared in Scientific American in 1973 and encouraged many people to learn more about cycling. The lengthy article was by SS Wilson, professor of engineering at Oxford University.

He wrote that the purpose of a bicycle was “to facilitate a person’s movement, and this the bicycle accomplishes in a way that far exceeds natural evolution.”

He argued, “When one compares the energy consumed in moving a certain distance as a function of body weight for a variety of animals and machines, one finds that a man walking unaided does quite well but is not as efficient as a horse or a salmon. However, with the help of a bicycle, the human energy consumption for a given distance is reduced to about one-fifth. Therefore, in addition to increasing his unaided speed by a factor of three or four, the cyclist improves his efficiency rating to number one among moving creatures and machines.”

https://youtu.be/4x8wTj-n33A

(This excerpt, and the accompanying graphic, inspired many others, including Apple’s Steve Jobs, who used it in a 1980 presentation to explain the efficiency of the personal computer: “What a computer is to me is the most remarkable tool we have ever thought of, and it is the equivalent of a bicycle for our minds.Wilson continued, “For those of us in the overdeveloped world, the bicycle offers a real alternative to the automobile.”

The bike’s simplicity coincided with EF Schumacher’s 1973 best-selling Small Is Beautiful. This was one of the eco-political critiques of the 1970s: it theorized that capitalism was inherently bad for the planet because, like a Ponzi scheme, it can only survive by growing, unsustainably. Instead, what was required, Schumacher believed, were “appropriate technologies” on a small scale.

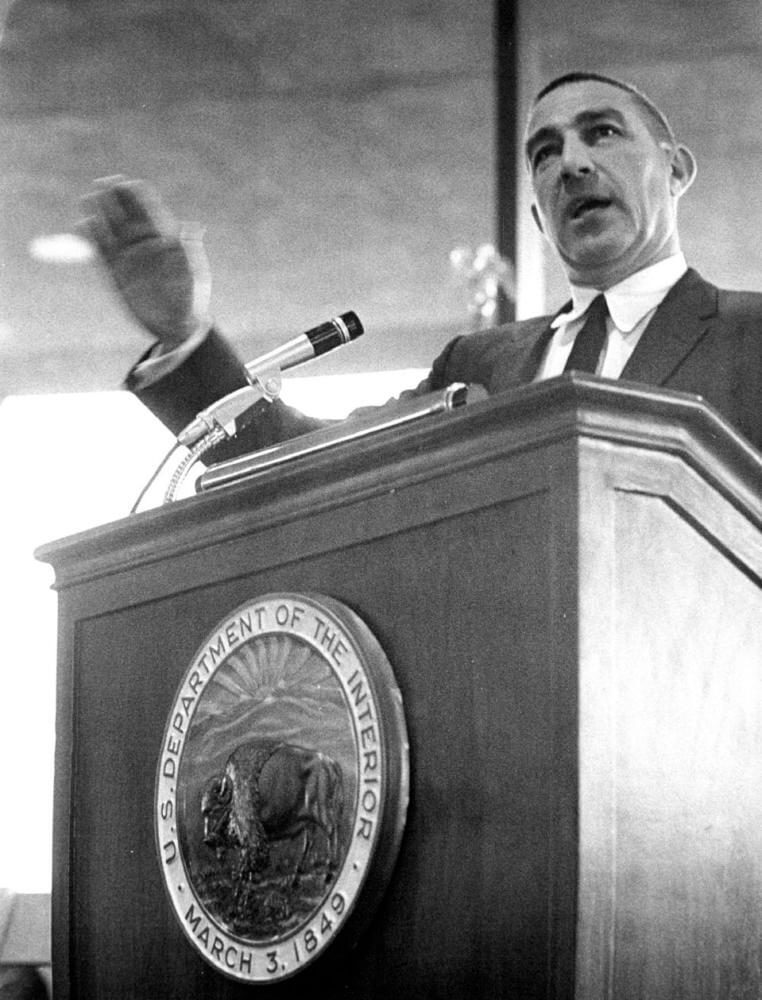

May 11, 1967, 6-6-1967; Udall L. Stewart

Stewart Udall in 1967. (Photo by Duane Howell / The Denver Post via Getty Images) DENVER POST VIA GETTY IMAGES

STEWART L.UDALL was one of the greenest American politicians of the 1960s; during his tenure as Secretary of the Interior, he commissioned a study that resulted in the Trails for America report, which promoted hiking trails in national parks, but also bike paths in cities: “To avoid crossing motor vehicle traffic, bike paths would be located along landscaped areas on the margins of secondary roads alongside highways, along coastlines, and on abandoned railroad rights-of-way,” the 1966 report envisioned.

Once out of the office, he was even more explicitly pro-bicycle. In 1973, he warned that President Nixon and Congress aim for fewer cars, fewer airline flights, but more bicycles and urban bike lanes. “We have to get away from the pretense that there is an easy, painless way to save energy,” Udall told the New York Times.“We are in the final stages of the climax of the automotive era. We have gone as far as we can. Give people choices, he said, build more bike lanes.

“People hold on to their cars because there is no alternative.”

The Bicycle Institute of America, a promoter of the industry, was one of many organizations frequently cited in the mainstream media in the early 1970s, thanks in part to its newsletter pushing bike lanes, Boom in Bikeways, which it had been sending to the media since the late 1960s.

The BIA, which also placed lifestyle ads in the press, boasted of the seemingly endless rise of the bicycle market. The good times were here to stay, many thought, including the authors who wrote best-selling zeitgeist hitters. Sex had Dr. Alex Comfort; cycling had Richard Ballantine.

Richard Ballantine

journalist and writer bicyclist February 1975

Richard Ballantine,Richard Ballantine, 1975. (Photo by WATFORD / Mirrorpix / Mirrorpix via Getty Images) MIRRORPIX VIA GETTY IMAGES

Richard ‘s Bicycle Book

was a publishing sensation in the 1970s; it sold more than one million copies. Ballantine connected to the politics of eco activism, which had encouraged many to ride bicycles.Ballantine’s book imagined a utopian future of bike lanes, but he didn’t think this would be enough to get more people cycling.

“Bike lanes are not enough“, he wrote.

“What is needed is the elimination of polluting transport. The absolute elimination of internal combustion engines from urban areas is the practical win-win solution.”Ballantine was the only son of publishers Ian and Betty Ballantine, creators of the New York paperback publisher Bantam, which popularized such artists as Tolkien, Arthur C. Clarke and Isaac Asimov. Her aunt was a radical political author. Ballantine grew up in a fog of new intellectual leftism.

“A better deal for cyclists,” he said, “is a better deal for society.”

When he argued that bicycles could change the world, he meant it, but he also told his readers that there would be a “long struggle,” because they were up against “the power of vested interests to maintain an age of the motor.” Richard’s bike book warned readers not to be too surprised if a policeman hits him on a bicycle and calls him a dirty communist.”

Two American children hold up a Bikeology poster mid 1970s

Bikeology poster, mid-1970s.

Two American children hold a Bikeology poster, mid-1970s.

BICYCLE INSTITUTE OF AMERICA

IN 1972, students at the University of Montana could choose between geology, psychology, biology or, new for that year, “Bikeology” “And for full credit, too,” claimed one newspaper, adding that this was “just another example of America’s love affair with the bicycle.” Students could even dress the part, since “special bicycle clothing for both sexes can be found in the elegant stores of all university towns.”

At the University of Iowa at Ames, the “three most popular subjects on campus were social change, cycling, and sex, in that order.” These university courses, and there were others at the universities of Texas, Utah and Oregon, studied the creation of bike lane master plans, including “how to pass bike lane legislation” and “how to integrate bike lane systems into urban planning.”

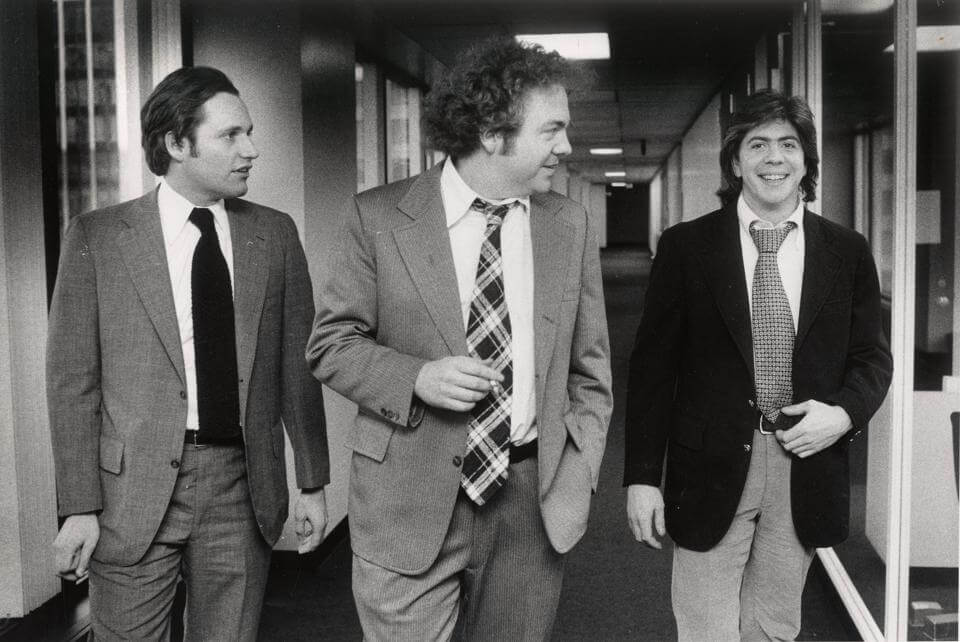

Bob Woodward Scott Armstrong and Carl Bernstein at the Washington Post 1975.

Bob Woodward, Scott Armstrong and Carl Bernstein in the Washington Post, 1975. (Photo by Margaret … [+] THE WASHINGTON POST VIA GETTY IMAGES

“WHEN CLAY GUBRIC opened Towpath Cycle Shop [in Washington, DC] in 1966, it had three or four cyclists pedaling home from work,” wrote a Washington Post staffer in 1970.“One day last week,” the reporter continued, “more than 50 cyclists in transit, most of them dressed in business suits or skirts, were passing by his store in Georgetown during the afternoon rush hour.”

The staff reporter was Carl Bernsteinone half of the famous Pulitzer Prize-winning partnership of Woodward and Bernstein, the investigative reporters who helped reveal the full scope of the 1972 Watergate scandal, which, two years later, led to President Nixon falling on his sword. Bernstein was the Washington Post’s “office hippie,” noted All the President’s Men, the pair’s book about the scandal that gave The World the suffix -gate.

Before they teamed up to work on what was, at first glance, thought to be a minor burglary at the Watergate hotel and office complex, Woodward pre-judged Bernstein to be a “long-haired, bicycle-riding monster.“. This was not an old bicycle. Bernstein, who was only a few months into his reporting job at the Post, had set out for the 1970 bicycle boom story because he was a DC cyclist himself. Bernstein traveled to and from work, and between assignments at the White House, in one of two ten-speed runners, either his Raleigh or his Holdsworth, both of venerable English makes.

The theft of Bernstein’s Raleigh bicycle became part of the Watergate story. “Bernstein knew something about bicycle thieves,” All the President’s Men revealed. “The night of the Watergate indictments, someone had stolen his ten-speed Raleigh from a parking lot. That was the difference between him and Woodward. Woodward went to a garage to find a source who could tell him what Nixon’s men were doing. Bernstein went into a garage to find an eight-pound chain neatly cut in two and his bicycle gone.”

As a hippie cyclist, Bernstein may have been expressing his own views when, in his 1970 Post article, he wrote that “many cyclists harbor a fierce antipathy for what they see as an automobile culture that is choking the nation with smoke, speed, noise and concrete.”

He added that there was a “growing group of cyclists who view pedaling as an almost political act and inevitably display the two-finger peace sign when meeting another person on a bicycle.” Bicycle facilities in Washington, DC, had been poor in the late 1960s, but had improved by the early 1970s, in part due to John A. Volpe, President Nixon‘s Secretary of Transportation. In 1969, Volpe, who habitually rode a bicycle that “you can fold up and take to your office on the tenth floor,” told Gilbert Hahn, the borough council president, to build bike lanes for Washington’s growing number of bicyclists who, like him, were not all long-haired hippies.

In fact, as Bernstein wrote in the Post, bike boom riders were equally likely to be “stockbrokers and congressmen, secretaries and lawyers, students and government employees, librarians and teachers, young and old.”

Transportation Secretary Volpe used to ride his folding bicycle from his home to Capitol Hill. At a meeting in 1971, he encouraged everyone “to use the legs that the dear Lord gave us [y a] to show what can be done with bicycles.” Volpe warned that cities needed to make “radical changes in their transportation patterns” to meet clean air standards, and suggested that bicycling would be a “valuable addition to urban transportation systems.”

He told the New York Times that the Department of Transportation would “do everything possible to establish dedicated bike lanes in our nation’s cities and along highways and freeways between cities.” Along with “150 dedicated cyclists,” Volpe rode in DC’s Rock Creek Park in May 1971, telling a reporter during the ride that cycling was“as much a means of exercise as a mode of transportation.”

Volpe added that his department intended to “make Washington a model city for bicycles.”

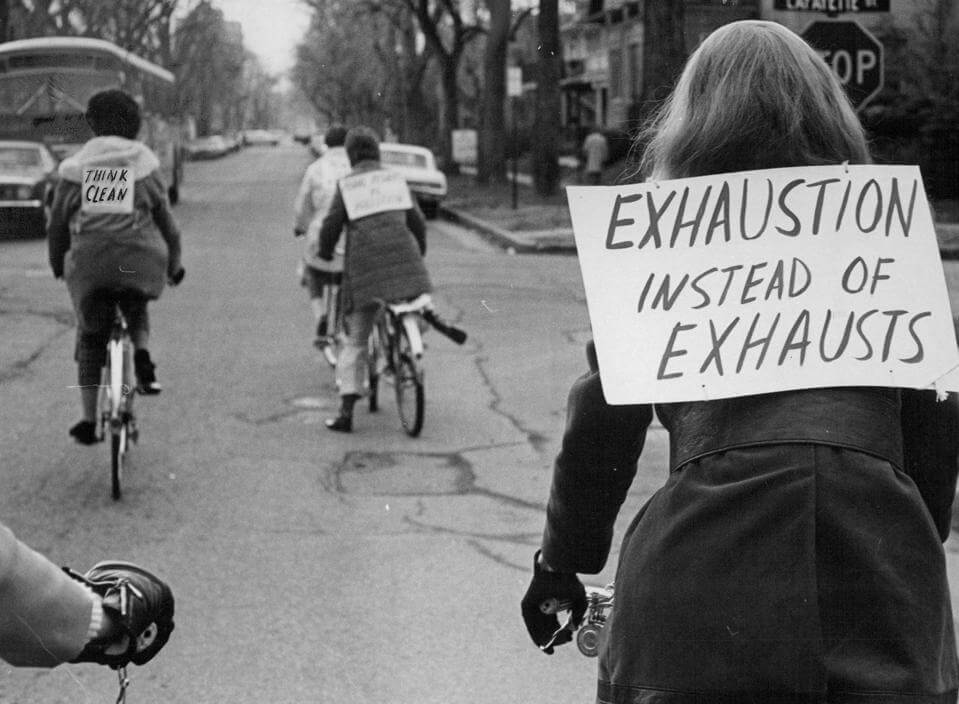

Gas mask wearing Nancy Pearlman Janice Jones Debbie Melville and Kathy Briggs

Nancy Pearlman in gas mask Janice Jones, Debbie Melville and Kathy Briggs

Later that year, hundreds of cyclists organized a “bike-in” on Beach Drive in DC, demanding more space. Not all were peaceful. As Bernstein wrote in his 1970 article, “some members of the cycling minority are becoming more militant.” He described how one driver was run off the road by the driver of a Buick Riviera who “drove off laughing.” The cyclist caught up with the smiling motorist and “alighted from his trusty 10-speed steed, the cyclist proceeded to kick a good-sized dent in the rear fender.”

Bernstein added that the motorist “watched helplessly as the pedal advocate remounted his bike, clenched his fist, and headed in the opposite direction with the words ‘Ride On‘”. (It is very likely that this militant cyclist was Bernstein, but despite many emails to his office, he has yet to say whether this is the case or not.)

Bicycle Institute of America newspaper ad.

Back to bicycling, urges a 1970s newspaper ad from the Bicycle Institute of America. BICYCLE INSTITUTE OF AMERICIn the early 1970s, going into a bike store was like going to a bank: you had to wait patiently in line. “The nation faces a serious bicycle shortage,” Time warned in the summer of 1971.

“Factories don’t make bicycles fast enough.“,

complained a San Francisco bike store. “If we order 100 bikes, we’re lucky to get 25.” A Los Angeles two-wheeler dealer told Time, “I can sell all the bikes I can own.” Bicycle ownership in the United States in the early 1970s was very low. Bicycles were intended for children, not adults; adults drove cars. This all changed when baby boomers started buying.

In the early 1970s, the post-World War II birth peak resulted in a glut of teenagers and 20-somethings. Many had cash, were eager for novelty, wanted independent mobility and were desperate to throw off the shackles of their elders.

In newspaper interviews at the height of the bike boom, industry leaders suggested all sorts of reasons for doubling the size of the market, but the most obvious: “the baby’s cry was heard around the country,” as historian Landon Jones described. trend – eluded them. “No one could have predicted [el auge],” said the president of a bicycle supplier chain in 1971. But the signs of population growth had been building for some time. Life magazine, in 1958, headlined the cover of one issue, “Children: Built-in Cure for Recession” and, referring to the retail potential of the growing number of American newborns, added,“How 4,000,000 a year generate billions in business.”

The magazine said the four-year-olds on its cover represented a “backlog of commercial orders that will take two decades to complete.”

More than 4 million babies were born each year from 1954 to 1964. By the 1970s, there were more than 70 million baby boomers in the United States, representing nearly 40% of the country’s population. Diapers had been the first product to increase; then, post-war parents used their new credit cards and credit accounts to buy refrigerators, televisions and, of course, family-sized cars.

The bicycle industry was taken by surprise when the demographic came to its products. It was a perfect storm, with baby boomers who dropped out of school and were attracted to cycling because of its anti-automobile environmentalism; suburban, conformist baby boomers latched onto cycling because it was healthy and they liked the outdoors; and pre-automobile teens upgraded to lightweight ten-speed bikes after being attracted to cycling because of “high-rider” bikes like the “cool” Schwinn Stingray from the 1960s.

Two young women ride Schwinn road bicycles 1970s.

Girls riding Schwinn bicycles

In 1971, 86% of Schwinn’s sales were full-size bikes, including the Varsity, a sturdy 40-pound handlebar bike with a derailleur and ten speeds.“Environmentalists are turning to the bicycle as a solution to pollution; Fitness fanatics like the bicycle to preserve the heart,” wrote Time in 1971.“Groups of workers in some traffic-clogged cities have been organizing rush-hour races between cars, buses and bicycles, with the bicycle generally triumphant.”

Industry consultant-and data fanatic-Jay Townley was a Schwinn executive in the 1970s and recalled that the bicycle industry had been surprised by the increase in sales. Domestic production could not meet demand, so the industry resorted to importing an increasing number of bicycles, many of which were unsatisfactory.

With the boom in full swing, there was no time to worry about where the demand was coming from, but after the inevitable collapse, when the market has halved in two yearsSchwinn tried to analyze where the sales were coming from. A 1978 three-volume strategic plan, maintained by Townley, detailed:

“This dramatic increase in bicycle speeds with 26- and 27-inch wheels in adult style can be largely attributed to young cyclists in the thirteen to seventeen year-plus segment of the population, who moved from the high-rise bike to the sophisticated lightweight derailleur-equipped bicycle.

Schwinn’s analysis coincided with that of safety consultant Dr. Kenneth Cross who, writing for an automobile organization in 1978, concluded rather blandly, “The so-called ‘bicycle boom’ that began in 1969 was due primarily to a dramatic increase in bicycle use by the teenage and adult population.”

Thanks to the 45 million bicycles sold at the height of the boom, the number of bicycle owners was now higher than ever. What was not said much by news sources at the time is that many of the bicycle purchases were due to contagion: people bought bicycles because they saw others buying bicycles. A large number of the ten speeds, impractical and terribly comfortable, gathered dust.

Cyclists Earth Day 197 Denver

Bicyclists of the, Earth Day, 1970, Denver. Credit: Denver Post

“We need to get past the stage of talking about the bicycle renaissance as if we are trying to convince ourselves that it really is a viable mode of transportation,” advised John E. Hirten, undersecretary of transportation in the inauguration of Bicycles USA in 1973, a federally sponsored conference that said it would help bicyclists find their “rightful place in the multimodal mix.”

Journalist Robert Reinhold wrote that “[el mensaje llegó] loud and clear at [la conferencia] that [el ciclismo] was” a possible solution to a whole galaxy of urban ills: congestion, pollution, fuel shortages and flabby muscles, to name a few.” Bicycles USA was co-sponsored by the Departments of Transportation and Interior and was held at the Transportation Systems Center in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

The two-day conference, which attracted 250 state highway planners, bicycle advocates, and government and law enforcement officials, was also attended by “several very happy bicycle manufacturers.”

CAMBRIDGE MASSACHUSETTS MARCH 20 A man bikes on the Dr. Paul Dudley White Bike Path on March

CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS – MARCH 20: A man rides his bicycle along the Dr. Paul Dudley White Cycle Route on March … [+] GETTY IMAGES

According to the Reinhold newspaper report, “an increasing number of cities are beginning to consider cycling as an important factor in commuting patterns.” And this new status for bicycling “has been echoed in Washington, where a marked awareness of bicycles has developed in recent months at the Department of Transportation,” said Marie Birnbaum, conference chair and head of the department’s bicycling (and pedestrian) division. .

At the conclusion of the conference, Hirten said, “I hope we can make the bicycle a reverse status symbol, the opposite of a large automobile.”

David Rowlands, writing for the influential British magazine Design, clearly had not visited the Netherlands, but he was impressed that a cycling conference had attracted such high-level support from the U.S. Department of Transportation: “What emerged from Bicycles USA was a more comprehensive response to an expanding cycling population than any other country currently offers. Government assistance has been an important factor in this new awareness of the potential of the bicycle as a means of transportation in the developed world. It is an example that deserves much wider imitation”.

In fact, the Department of Transportation was about to do its own imitation. Or, at the very least, I would send a transportation engineer to Europe to find out if the United States could learn any lessons from what was happening in cycling countries like the Netherlands.

Julie Anna Fee of the DoT was sent to Europe in May 1974. May 1974 and wrote a report on how pedestrians and cyclists were treated in some European countries. European Experience in Pedestrian and Bicycle Facilities reported that “Europeans [were] returning residential areas to residents and restricting the through movement of automobiles in these areas.”European experience with pedestrian and bicycle facilities reported that “Europeans [estaban] returning residential areas to residents and restricting automobile circulation in these areas.” Fee highlighted the fact that increasing car use had forced some people to give up bicycles, but that “most planners in European cities hope to achieve a resurgence of bicycle transportation by installing separate bicycle facilities.”

Amsterdam, he wrote, “is investigating ideas and techniques to encourage cycling. It is interesting to note that in the‘bicycle city‘ the method that will be used to stimulate the bicycle renaissance is to institute an extensive system of separated bike lanes. There is generally not enough space on the street to provide a bicycle lane. Therefore, in many cases, entire streets will be closed to motor vehicle entire streets will be closed to and designated for exclusive use by cyclists and moped riders.”

He added that the growth of cycling in the US. He suggested that the nation should accelerate its provision for cyclists: “Cycling in Europe is much more extensive than in the United States. However, the trend of bicycle use is decreasing, unlike the increase in the United States.”

A major U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) report, also published in 1974, concluded that the United States should emulate the Netherlands and build urban bikeway networks.

Bicycle Transportation praised bicycle facilities in Europe and said, “The United States is experiencing an unprecedented boom in bicycle sales and use. In 1972, bicycles outsold automobiles by 2 million. The federal government is beginning to recognize bicycles as a viable form of transportation.”

The EPA report noted that “40% of all urban work trips made by automobile are 4 miles or less. These short trips can easily be made by bicycle at 13 mph in less than 20 minutes.”

What would get more people on bikes, the report asked? The answer seemed obvious: “38% of bicycle owners said they would travel by bicycle if safe bike lanes and secure parking were available. Of those who do not own bicycles, 17 percent said they would buy a bicycle for commuting if there were bike lanes and bicycle parking.”

Significantly, the EPA also said that “there would be a greater number of automobile commuters who would convert to bicycles if tighter automobile restrictions were imposed.” Spending on cycling had to be increased because “bikeway construction and better law enforcement are public goods that require government involvement.” That year, 1974, was the peak year for government interest in cycling because, in addition to the EPA report and the European experience report, the Department of Transportation’s first cycle infrastructure style guide was published.

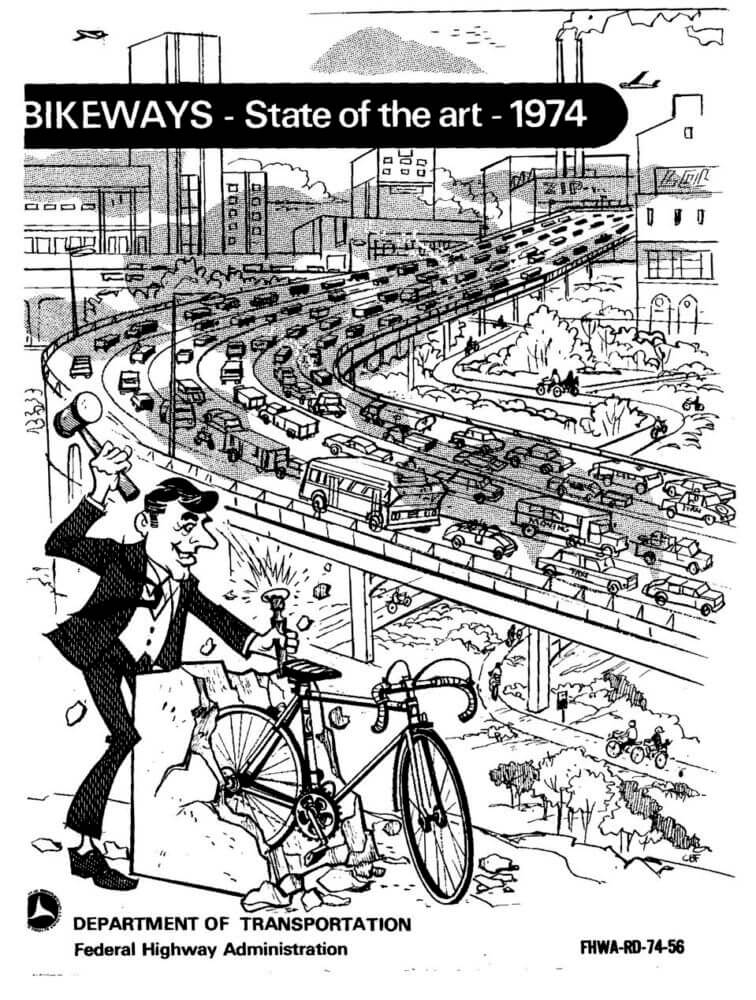

Bikeways-State of the Art 1974 by the Department of Transportation. DOT 1974

“Bicycle Lanes – State of the Art, 1974” by the Department of Transportation. DOT, 1974

Bike Lanes: State of the Art 1974 was produced for DoT by an outside contractor and published in the summer. The 97-page report was “intentional. . . as the first source of reference for communities carrying out bikeway programs”. A cartoon on the cover showed traffic snarled on an elevated road with separate bike lanes snaking underneath, and a ten-speed bicycle was chiseled out of rock by a man in a suit.

The report included information on “protected lanes that provide positive physical separation between bicycles and motor vehicles rather than simple delineation of markings,” and praised the type of rough-and-ready infrastructure provision now known as “tactical urbanism,” and widely used by cities around the world during the current pandemic.

“In Sausalito, California, planters have been deployed as lane delineation buffers,” the EPA report said. “In this era of energy scarcity, air and noise pollution, and rising costs, the bicycle offers a quiet, economical, and non-polluting alternative to the automobile,” the plan states. “But just as the automobile has needed support programs from its early development years to its current stage of maturity, the bicycle needs them now.”

In Los Angeles, a bikeway plan wanted to create a “1501-mile network of facilities, one that will be available to anyone who chooses to use it,” and emphasized “separation from vehicular traffic.” “Intersections are a big problem,” the plan acknowledged. “Turning vehicle operators may not see the cyclist or may choose not to respect their right-of-way. This is a problem with all types of bicycle facilities, including a separated bicycle lane that crosses a road. Even expensive grade separations have not proven to be effective in some areas, as cyclists will avoid them if they are not convenient.”

Period graph showing the rise and fall of bicycle sales in the 1970s.

Period graph.

Period graph showing the rise and fall of bicycle sales in the 1970s.

BICYCLE INSTITUTE OF AMERICA LOS ANGELES’ bikeway plan was ambitious, but it was too late. It was published in 1975, the year the boom exploded. Bicycle sales in the U.S. dropped by half in a few months.

Despite the obvious boost to cycling in the United States from the OPEC oil crisis of 1973, when fuel was scarce and getting around by car became expensive and, due to speed restrictions to save oil, slower, cycling had not changed the world.

John Volpe, a friend of bike lanes, left the Department of Transportation to become U.S. ambassador to Italy. State highway planners endorsed what had been grandiose bikeway plans. The queues at the bike stores were reduced to nothing. Bicycle manufacturers cancelled overseas orders. The bicycle boom, and the nation’s interest in bicycles, was over.

“The boom has turned into a bust.”,

admitted the president of the Bicycle Manufacturing Association of America before the Senate Finance Committee in 1976.

The assistant secretary of transportation who had opened the Bicycles USA conference in 1973 had seen this coming. John Hirten, an urban planner before he was appointed to his DoT post, had warned that the Great American Bicycle Boom, wonderful as it is, could backfire: “The danger is that bicycling will become the hoop of the 1970s. “

Former Schwinn executive Jay Townley believes that if the bike boom had continued, if annual sales of adult bikes had remained at 15 million for perhaps another year or two, some of the dreams of many bike advocates might have come true:

“If the bicycle boom had continued, America might look very different today.”

Berlin street empty of cars during the 1973 oil crisis

Fahrverbote, Ölkrise, Deutschland: Strasse des 17. Juni, Berlin, 25.11.1973

Berlin street without cars during the 1973 oil crisis

But the boom did not continue. Why? The reasons are complex, but include the fact that bicycles sold at the height of the U.S. boom were poor quality imports, deflating the desire to ride. It was also the case that environmentalists moved on to other issues, such as anti-nuclear campaigns and saving the whales.

Perhaps the most important reason was the hoola-hoop effect: cycling in the 1970s had been a craze, and those who were attracted to it were not sufficiently sold on the idea to continue riding long term, either recreationally or, critically, for Dutch-style daily transportation.

The automobile did not die; America continued down the path of automobile dependence. The COVID-19 blockade has shown that a different future is possible: if we control the car. Automobiles dominate because decisions were made to allow such dominance. Decisions can be remade; minds can be changed.

And now it’s time for cities to be bold, and many, like Milan, Paris and Oakland, California, are being bold, taking space away from cars and giving it to pedestrians and cyclists. Coronavirus cases drop in Italy after weeks of blockade

A cyclist rides along the new bike lane installed by the municipality of Milan on Corso Venezia

A cyclist rides along the new bike lane installed by the municipality of Milan on Corso Venezia

The struggle to create cities where people come first has long been a struggle against vested interests, a struggle against inertia, a struggle against the “this is the way it is” engine. But, as we have seen during the closure, streets can be changed, and they can be changed radically and for the better.

A revealing and inspiring exercise is to look at “then” and “now” photographs of Dutch streets. Many were clogged with cars in the 1970s, but then decisions were made to reshape the streets, blocking automobile access. Today these streets are designed for people, not cars, which makes many people assume that they were always this civilized. They were not.

2020 bike boom could have a more lasting impact in cities around the world than that of bicycles in the 1970s in the United States. But only if planners and politicians – and the people – clamor for this change.

Adapted from a chapter in Bike Boom, Carlton Reid, Island Press, Washington, DC, 2017..